5 Quarters Later: An Examination of Denver’s Inclusionary Housing Ordinance

It would be a safe bet to say that most real estate professionals, especially those of us who work in housing, are aware of the City and County of Denver’s (Denver’s) current inclusionary housing ordinance, know as “Expanding Housing Affordability” (EHA). According to Denver’s website, the EHA project started in 2020 and over a two-year period, city staff worked with various stakeholders from both the public and private sectors to develop a new inclusionary housing policy. In May 2021, Governor Polis set the table for inclusionary housing when he signed HB21-1117, allowing local governments to require developers to include affordable units in new projects. The first draft of the policy was issued on October 1, 2021, and after numerous discussions and public meetings, Denver City Council voted to approve the EHA on June 6, 2022. The EHA became effective on July 1, 2022, although projects that were in the city’s development process before that date were allowed a specified period to finish permitting without triggering the new affordability requirements.

The details of the policy are somewhat complicated, but in simple terms, the EHA requires all residential developments of 10 or more units to include a specified ratio of affordable housing (i.e., subsidized by the developer and/or the other residents) for a period of 99 years, regardless of whether the home is for rent or for sale. For rental properties, the policy requires 8% to 10% of total units to be subsidized for renters at 60% of the Area Median Income (AMI) or 12% to 15% of total units to be subsidized with an effective average of 70% AMI, depending on a project’s location. In return for these subsidized units, Denver offered certain incentives, such as reductions in required parking ratios and reductions in certain fees, including reduced permit fees and linkage fees. Notably, the inducements did not include significant financial incentives, such as tax abatement. And while there is a fee-in-lieu option, it was admittedly designed to be expensive enough to try to motivate developers to build the required affordable units rather than buy their way out. The end goal of this well-intentioned policy was to create more affordable housing units by piggybacking on Denver’s recent development boom.

To be clear, we are not developers, and, as such, we have no “skin in the game” with regard to this policy. And while we recognize the vital need for more affordable housing, as appraisers

and market analysts, we are committed to calling balls and strikes. From the beginning, we were concerned about the negative impact this policy would likely have on development in Denver because it fundamentally requires market rate renters to subsidize rents for their neighbors. Prior to the approval of the ordinance, we shared our concerns regarding the likely unintended consequences of enacting such a policy with planning staff and Denver City Council members, but to no avail.

Specifically, we predicted that the policy, as enacted, would have a significant negative impact on the financial feasibility of most, if not all, market rate apartment development within Denver and that many fewer units would be proposed in Denver over the next few years. Put another way, we were concerned that the policy would effectively turn off the spigot of development in Denver moving forward. This is because the model required by the EHA simply doesn’t work as it requires (a) the majority of renters to pay above-market rents in order to subsidize the units with below market rents, or (b) developers to lower their targeted rates of return - in reality, likely both. Neither of these scenarios works because renters, by definition, will not pay above market rents, and developers barely achieve financial feasibility in the current market without these new affordability requirements.

A significant reduction in the Denver pipeline would be especially problematic because, since 2010, nearly 50% of all new apartments in the 7-county metro area were built in the City and

County of Denver. If we disincentivize development of apartments in the most prolific county in the metro area, there will be significantly fewer units delivered after the current under construction pipeline is completed. If demand remains strong and supply is reduced significantly, Economics 101 teaches us that rents will again begin to rise quickly, much as they have for the past 10 years. In order to avoid the requirements of the EHA, many developers scrambled to get applications into Denver’s planning department before the EHA took effect. As shown on the graph on the previous page, developers applied for 3,726 conventional units in Denver in the 4th quarter of 2021, ramping up to 8,562 conventional units in the 1st quarter of 2022, then nearly doubling to 16,408 conventional units in the 2nd quarter of 2022 leading up to the June 30th cut-off. Then, as predicted, the number of conventional unit applications fell precipitously.

To simplify this analysis, we have assumed that all new market rate developments in Denver would include 10% of their units at 60% AMI. As illustrated, unit applications in Denver plummeted to 1,524 units (including an estimated 1,370 market rent units and 154 affordable EHA units) during the 3rd quarter 2022. Applications fell further to 833 units (749 market rent and 84 affordable EHA units) and 1,258 units (1,133 market rent and 125 affordable EHA units) in the 4th quarter 2022 and 1st quarter 2023, respectively. Finally,applications bottomed out at 450 units (405 market rent and 45 affordable EHA units) in the 2nd quarter 2023. This was again followed by 464 units (418 market rent and 46 affordable EHA units) in the 3rd quarter 2023, compared to more than 16,400 units applied for 5 quarters prior (2nd quarter of 2022). during the same quarter the year prior. Although the EHA was intended to significantly increase the number of affordable apartments, it is, in reality, set to add a disappointing total of approximately 454 affordable units to date, while at the same time decimating future apartment development in Denver.

To be fair, the unit applications in the quarters leading up to the EHA deadline were inflated. As the deadline approached, developers rushed into planning before the EHA took effect. As a result, many were not funded and are not likely to be built. The subsequent decline in applications is therefore exaggerated because many of the projects that were rushed into planning may have otherwise applied in the subsequent quarters. Nonetheless, the very small number of applications over the past five quarters compared to historical applications is clearly related to the impact of the EHA.

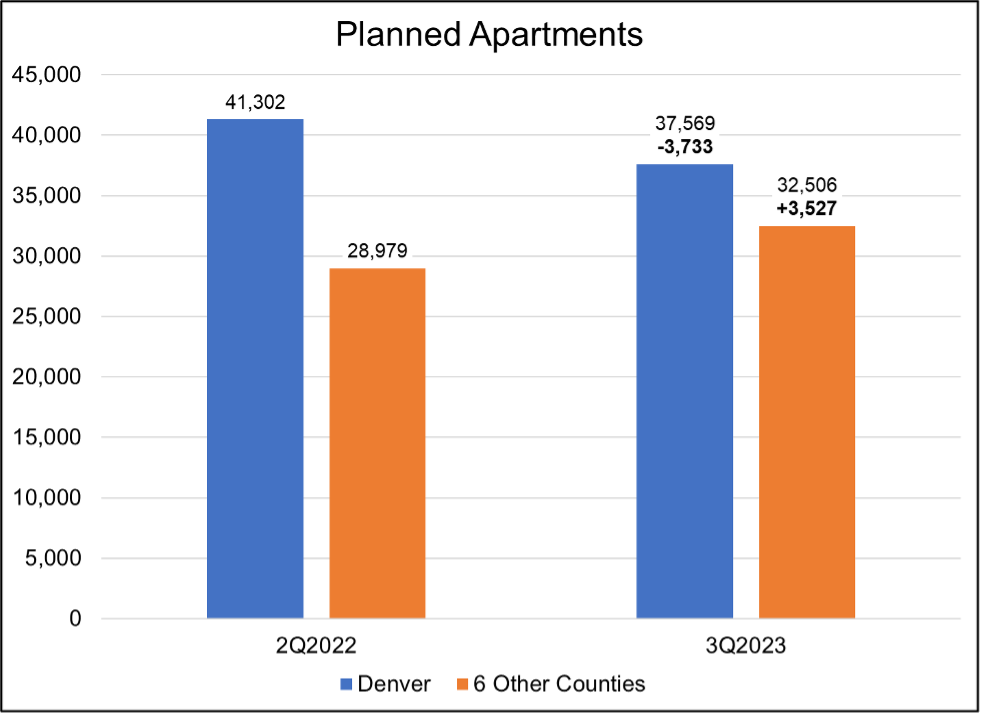

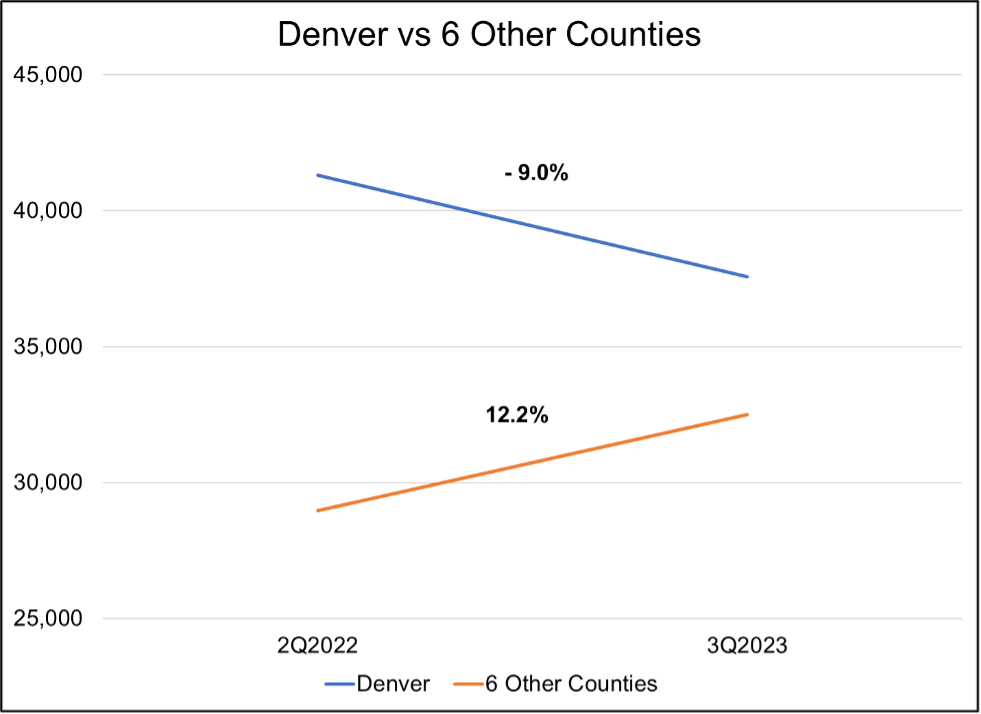

When presented with this information, defenders of the EHA say that the results shown above are not due to the inclusionary housing policy, but are instead the result of macroeconomic and other factors, such as increasing construction costs, lack of labor, supply chain issues, and increasing entitlement/ inspection periods, as well as, more recently, increasing interest rates and inflation. As a test of these arguments, we have analyzed the number of new applications in Denver compared to the new applications in the surrounding 6 metro area counties. As shown in the following graphs above, the overall pipeline of proposed apartments in Denver fell 3,733 units (down 9.0%) from the 2nd quarter 2022 to the 3rd quarter 2023, while the pipeline in the other 6 counties increased by 3,527 units (up 12.2%) during the same period. If the negative change in Denver were solely the result of the common factors discussed above, one would expect similar negative impacts on the proposed pipeline in the other 6 counties. However, while the Denver pipeline is down 9%, the pipeline in the other 6 counties is up more than 12%. This demonstrates that the EHA has had a negative impact on the proposed pipeline in Denver.

It appears that the number of units currently in the Denver pipeline is likely to continue to shrink. First, the developer success rate (i.e., the ratio of units proposed at the beginning of the year that actually break ground during the year) in the metro area has fallen significantly over the past few years, due to the macroeconomic and other factors mentioned above, and is projected to continue falling. This will reduce the number of units being delivered in 3+ years. Second, many of the projects that entered planning prior to the EHA deadline did so without sufficient due diligence, which indicates that some (perhaps many) are not based on strong fundamentals and are likely to be dropped by developers. In fact, more than a few of these rushed projects that were grandfathered have already been dropped.

Finally, if properties currentlyin planning don’t receive a final site development plan (SDP) approvalby the relevant deadlines, they will lose their exemption from the EHA’s affordable requirements and will likely no longer be financially feasible. Final SDP approval was originally required by the end of August 2023 or December 2023, depending on the size/ type of project. However, in May 2023, Denver City Council extended those deadlines to mid-May 2024 and mid- September 2024, respectively, with possible additional extensions through the end of August 2024 and December 2024. These extensions were necessary because the significant number of projects that applied prior to the EHA deadline overwhelmed Denver’s planning department. Denver Planning and Development simply could not get through the applications timely. These future SDP due dates will be telling as to how many units in the Denver pipeline move forward and how many eventually fall out. As the analysis above illustrates, if projects that are currently exempt from the EHA requirements fall out, there almost certainly will not be additional projects to backstop them.

There were nearly 46,000 units under construction in the 7-county metro area as of the 3rd quarter 2023, all of which will deliver over the next few years. As those units are delivered, vacancy throughout the metro area is likely to increase and rental growth is likely to slow. However, after these apartments are completed, we expect future deliveries to shrink as a result of the EHA. The shrinkage will be further exacerbated if surrounding communities adopt similar policies. So, when demand begins to significantly exceed supply again beginning around 2026, and rents skyrocket, we must all remember why and try to learn from our past mistakes.

Other municipalities throughout Colorado are considering implementing similar inclusionary housing ordinances, and a few have already implemented similar policies. However, the case study in Denver should act as a cautionary tale to officials throughout the state, and across the country, that such policies do not work as intended. The unintended consequences do not outweigh the relatively small increase in affordable units that they generate. Further, if other municipalities similarly disincentivize market rate apartment development, there will be even fewer apartments built in the future, causing an even bigger housing affordability crisis throughout the region. There is no question that there truly is a significant need for additional affordable housing in Denver and throughout the 7-county metro area.

However, we believe the development community, municipalities, and voters should instead focus their time, effort, and financial resources on trying to expand the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, or similar programs, which have proven to work well and provide affordable housing in a financially feasible manner.

Updated from an article originally published in the August 2, 2023 issue of Colorado Real Estate Journal